The Chandrayaan-3 mission has propelled India into the position of being the first nation to successfully reach the intact lunar south polar region. This accomplishment stands as another remarkable milestone for India’s indigenous space program. Two robots from India, named Vikram (the lander) and Pragyan (the rover), executed a controlled descent and landing in the southern polar expanse of the moon on Wednesday. This success firmly establishes India as the pioneer in achieving such a feat, marking it as the fourth nation in history to accomplish a moon landing.

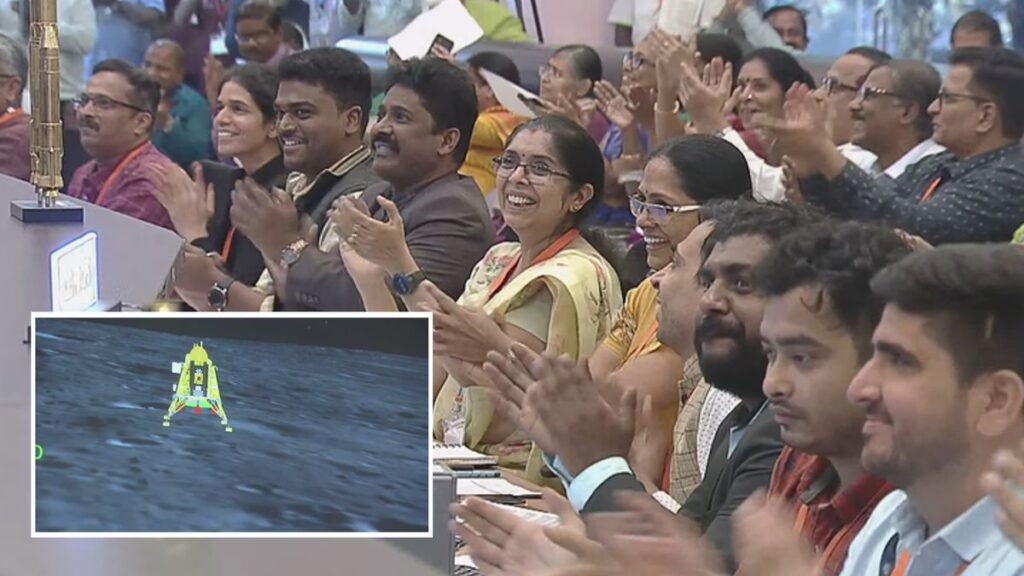

S. Somanath, the chairman of the Indian Space Research Organization, announced amidst jubilant cheers that “We have achieved a soft moon landing.” The exclamation echoed through the ISRO compound shortly past 6 p.m. local time. He proudly stated, “India has set foot on the lunar surface.”

India’s citizenry already takes immense pride in the nation’s space achievements, including successful lunar and Martian orbiters, as well as cost-efficient satellite launches that outshine those of many established spacefaring nations. However, the achievement of Chandrayaan-3 bears distinct significance, perfectly aligning with India’s strategic aspirations on the global stage, particularly during a critical juncture when the nation is asserting its ambitions as a burgeoning power in South Asia.

At this juncture, Indian officials are fervently advocating for a multipolar world order, positioning New Delhi as a crucial player in offering global solutions. This narrative, championed by Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s administration, emphasizes that India’s leadership can contribute to a more equitable world, even as the populous country remains dedicated to addressing fundamental needs.

This resolute international stance mirrors Mr. Modi’s central campaign theme as he approaches a potential third term in office. He has consistently intertwined his image with India’s ascent as a formidable economic, diplomatic, and technological force.

Mr. Modi has personally presided over pivotal milestones in India’s space endeavors, notably during the successful Mars orbit insertion in 2014 and the poignant moon landing attempt in 2019 where he consoled scientists and embraced the head of ISRO, who was visibly moved.

However, the Chandrayaan-3 landing happened to coincide with Mr. Modi’s visit to South Africa for a BRICS nations meeting. During the final moments of the landing, his visage was broadcast into the Bengaluru control room, sharing the screen with the animation of the lander.

When the landing was confirmed, Mr. Modi proclaimed, “Chandrayaan-3’s triumph mirrors the aspirations and capabilities of 1.4 billion Indians,” hailing the event as a “defining moment for the emerging, progressive India.”

Amid India’s rich scientific heritage, the anticipation surrounding the landing created a rare instance of unity amidst times marked by sectarian tensions exacerbated by divisive policies of Mr. Modi’s Hindu nationalist party. Prayers reverberated through Hindu temples, Sikh Gurdwaras, and Muslim mosques, while schools arranged special ceremonies and live screenings of the moon landing, with the official YouTube video garnering millions of views. Mumbai’s police band even performed a “special musical tribute” to the scientists, playing a popular patriotic song.

The Indian mission initiated in July, opting for a fuel-efficient trajectory toward the moon. Remarkably, Chandrayaan-3 outlasted its Russian counterpart, Luna-25, which had launched merely 12 days earlier. Regrettably, Luna-25 experienced an engine malfunction and crashed on its planned lunar landing attempt.

India’s outperformance of Russia, a nation renowned for its space exploits, underscores the contrasting trajectories of the two countries’ space endeavors.

While much of India’s foreign policy historically navigated a delicate equilibrium between Washington and Moscow, the nation is increasingly grappling with a more assertive China at its borders. A prolonged military standoff in the Himalayas has cast a shadow, driving India’s strategic calculus and amplifying the need to address potential Chinese threats.

This shared concern has fostered deeper collaboration between the United States and India, particularly in space, where China poses a direct challenge to American supremacy.

The success of Chandrayaan-3 augments Mr. Modi’s ability to leverage India’s scientific prowess for advancing national interests on the global platform, as outlined by Bharat Karnad, a distinguished professor of national security studies in New Delhi.

The Bengaluru control room transformed into a jubilant scene as engineers, scientists, and technicians from ISRO celebrated the triumphant achievement.

Following the landing, ISRO leaders shared that the setback of the previous moon landing attempt in 2019 significantly propelled their relentless efforts toward Chandrayaan-3.

Kalpana Kalahasti, the mission’s associate project director, shared, “From the moment we embarked on rebuilding our spacecraft after the Chandaryaan-2 experience, Chandrayaan-3 has been the pulse of our team.”

Since early August, Chandrayaan-3 had been in lunar orbit, and a meticulously planned series of maneuvers, executed on Wednesday, facilitated the controlled descent. The lander’s engines initiated the “rough braking” phase, causing its speed to increase during the descent. After 11.5 minutes, the lander hovered roughly 4.5 miles above the surface, transitioning from horizontal to vertical orientation as it continued its descent.

Hovering approximately 150 yards from the surface for a brief period, the spacecraft then gently settled on the lunar terrain, roughly 370 miles from the south pole. This complex landing sequence unfolded over 19 minutes.

Chandrayaan-3, primarily a scientific mission, was meticulously timed to coincide with a two-week period when sunlight would energize the lander and rover through solar panels. These two components will employ a range of instruments to measure thermal, seismic, and mineralogical properties.

India’s future in space remains promising, with numerous endeavors on the horizon. While an Indian astronaut had ventured into space aboard a Soviet craft in 1984, India has yet to send its own crewed mission. The Gaganyaan project aims to remedy this, planning to send three Indian astronauts into space using the country’s spacecraft. However, the project has experienced delays, and ISRO has refrained from specifying a launch date.

Furthermore, India is actively working on deploying a solar observatory named Aditya-L1 in early September, as well as collaborating with NASA on an Earth observation satellite. A follow-up mission to its successful Mars orbiter endeavor is also in the pipeline.

Mr. Somanath characterized this juncture as pivotal, signifying India’s shift from a state-controlled monopoly to engaging private investors in its space ventures. He highlighted the cost-effectiveness of these missions and, with a touch of humor, declined to disclose Chandrayaan-3’s cost to the press.

While ISRO continues its celestial explorations, India’s private sector achievements are rapidly gaining prominence. A new generation of space engineers, inspired by SpaceX, is venturing into business, with India’s private space economy already exceeding $6 billion and predicted to triple by 2025.

Change is accelerating, with Mr. Modi’s government aiming to harness the private sector’s entrepreneurial energy for more rapid satellite launches and increased investment in space.